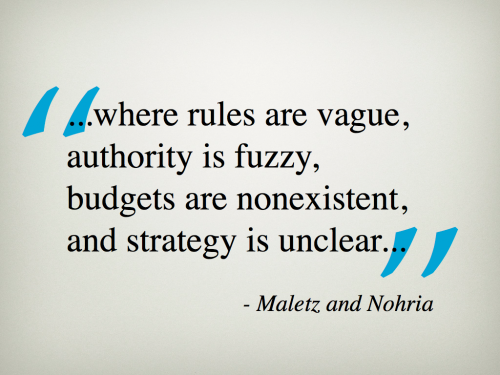

Whitespace in business is defined as a place, “…where rules are vague, authority is fuzzy, budgets are nonexistent, and strategy is unclear…” It’s the space between the organizational chart, where the real innovation happens. It’s also a great definition for what we see in Africa, and it’s the reason why it’s one of the most exciting places to be a technology entrepreneur today.

I just finished with a talk at PopTech on Saturday where I talked about “The Idea of Africa” and how Western abstractions of the continent are often mired in the past. It’s not just safaris and athletes, poverty and corruption – it’s more nuanced than that.

Today I’m in London for Nokia World 2011 and am speaking on a panel about “The next billion” and how it might/might not turn the world upside down. In my comments tomorrow, I’ll probably be echoing many of the same thoughts that came out over the weekend at PopTech.

Here are a few of the points that we might get into tomorrow:

Horizontal vs Vertical scaling

I talk a lot about this with my friend Ken Banks, where we look to scale our own products (Ushahidi and FrontlineSMS) in a less traditional format. As entrepreneurs you’re driven to scale, but our definition of scale in the West tends to be monolithic. Creating verticals that are incredibly efficient, but which decreases resilience.

In places like Africa, we have this idea of horizontal scaling, where the product or service is grown in smaller units, but spread over multiple populations and communities. Where a smaller size has its own benefits.

In this time of corporate and government cuts, where seemingly oversized companies are propped up in order to not fail, there are some lessons here for the West. We shouldn’t be surprised that the solutions to the West’s problems will increasingly come from places like Africa.

Instead of thinking of Africa as a place that needs to be more like the West, we’re now looking at Africa and realizing the West need to be more like Africa.

Reverse distribution

Will we increasingly see a new set of innovative ideas, products and services coming from places like Africa and spreading to the rest of the world? Why is Africa such a fertile ground for a different type of innovation, a more practical one – or is it?

Disruptive ideas happen at the edge.

Africa is on the edge. While the world talks at great length about the shifting of power from the West (US/Europe) to the East (India/China), Africa is overlooked. That works in our favor (sometimes).

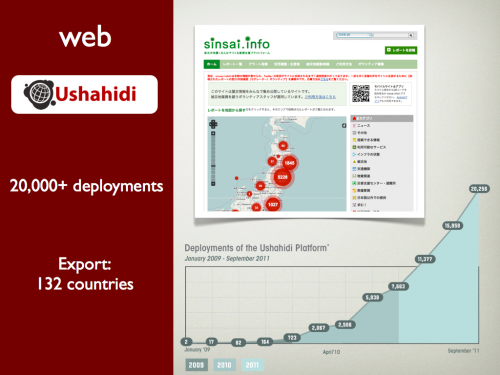

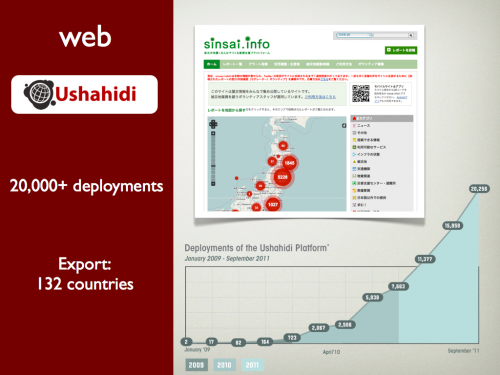

A couple of the ideas and products that have started in Africa and been exported beyond the continent include; Mpesa, Ushahidi and Mxit.

Mpesa – the idea came from Vodafone, but product met it’s success in Kenya. Over $8 billion has been transferred through it’s peer-to-peer payment system. Vodafone has failed to make the brand go global, but the model itself is being dissected and mimicked the world over.

Ushahidi – we started small, from Kenya again, and driven by our Crowdmap platform now have over 20,000 deployments of our software around the world. It’s in 132 countries, and the biggest uses of it are in places like Japan, Russia, Mexico and the US.

Mxit – the famous mobile chat software from South Africa has 3x the number of Facebook users in that country, and has over 25 million users globally.

Like we see at Maker Faire Africa, these innovative solutions are based on needs locally, many of them due to budgetary constraints. Some of them due to cultural idiosyncrasies. Often times, people from the West can’t imagine, nor create, the solutions needed in emerging markets, they don’t have the context and the “mobile first” paradigm isn’t understood.

A good example of this is Okoa Jihazi, a way to get a small loan of credit for your mobile phone minutes when you’re out of cash to buy them, from the operator. They’ve built some safeguards in to protect against abuse, such as you have to have had the SIM for 6 months in order to get the service. It works though, because the company selling it (and many of the mobile operators do across Africa) understands the nuanced life of Africa.

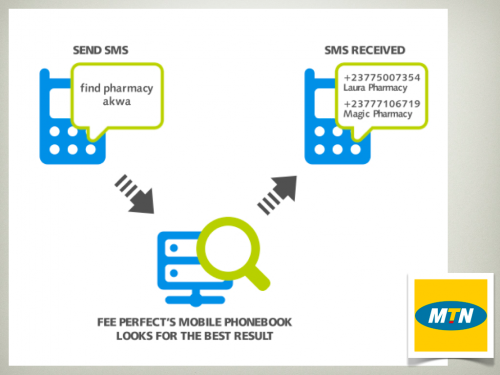

We hold on to technology longer, experiment on it, abuse it even. SMS and USSD are great examples of this, while much of the Western world is jumping on the next big technology bandwagon, there are really crazy things coming out in emerging markets, like USSD internet, payment systems, ticketing and more.

Throughout the world, the basic foundation of any technology success is based on finding a problem, a need, and solving it. This is what we’re doing in Africa. We have different use cases and cultures, which means that there will be many solutions. Some will only be valuable for local needs and won’t scale beyond the country or region. Others will go global. Both solutions are “right”, it’s not a failure to have a product that profitably serves 100,000 people instead of 100 million.

Turning the world upside down has as much to do with accepting this idea of localized success as an acceptable answer as it does with explosive global growth and massive vertical scale.

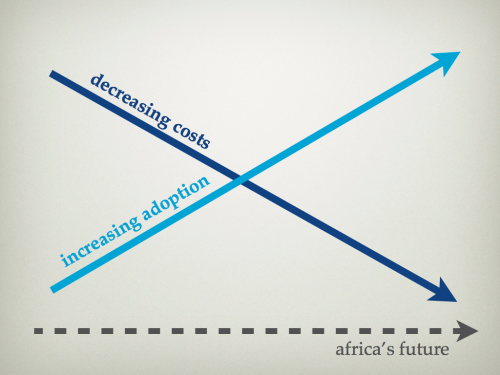

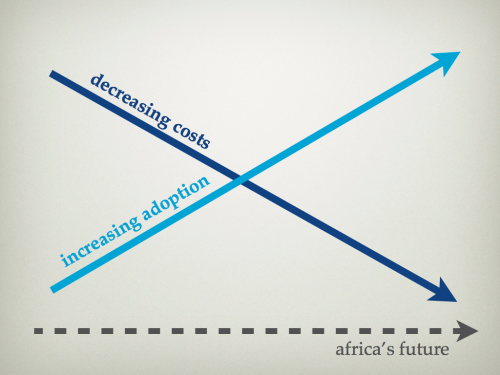

The Two Big Trends

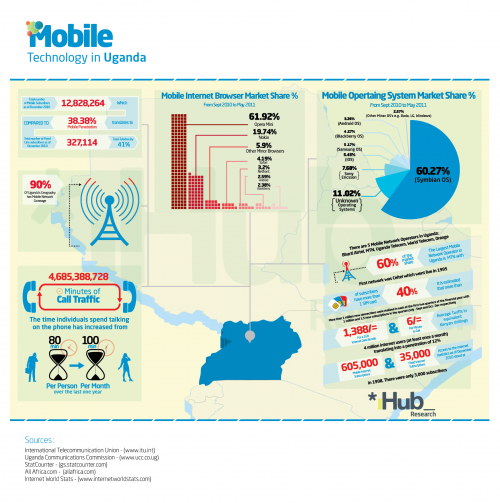

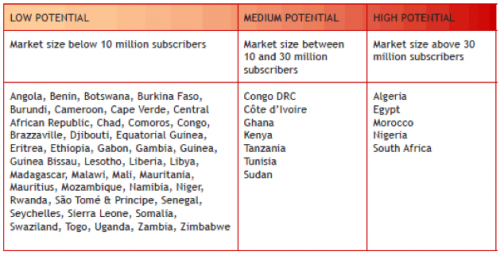

Trend #1: Adoption by Africans as consumers is increasing.

Trend #2: Technology costs are decreasing

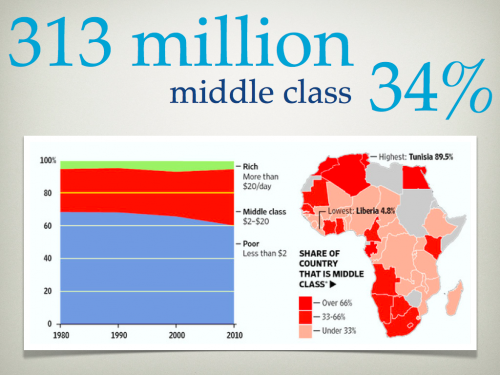

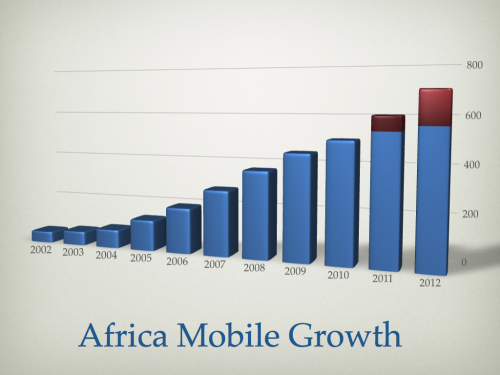

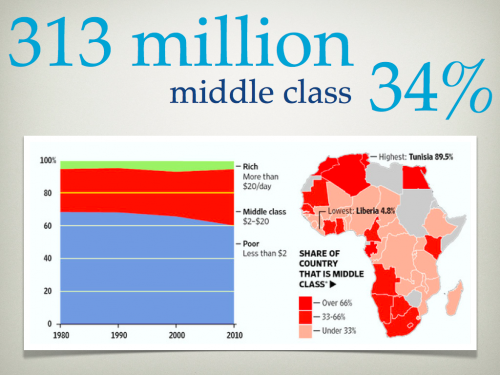

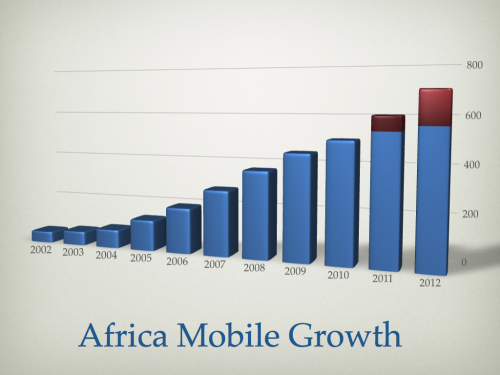

Let’s get back to my talk for tomorrow at Nokia… 87% of sub-$100 phones sold by Nokia are sold in emerging markets. 34% of Africa’s population (313 million) are now considered middle class. The fastest growing economy in the world is Ghana, 5 of the top 10 are African countries (including Liberia, Ethiopia, Angola and Mozambique). Across the continent, the average GDP growth is expected to be at 5+% going forward.

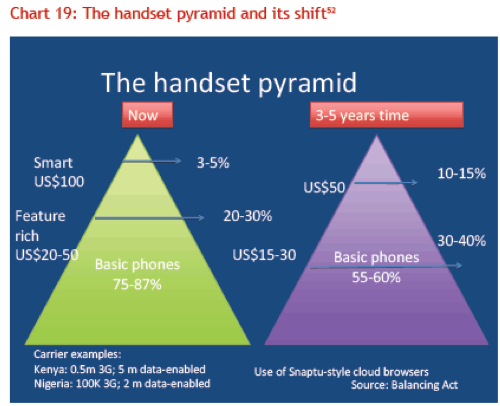

At the same time, we’re seeing bandwidth increase, and bandwidth costs decrease. Mobile operators are the continents major ISPs, and they’re getting creative on their data plans. Handset costs are going down. Smart(er) phones are available for less than ever before. We even have one of the lease expensive Android phones in the world at $80 in Kenya, the IDEOS by Huawei.

Is it all bright and rosy? Not at all. You’re on the edge, you have to create new markets, not just new businesses. But in that challenge lies opportunity, for it’s from these hard, rough and disruptive spaces that great wealth is grown. If you’re an African entrepreneur, why would you want to be anywhere else?