For the past 6 years I’ve been part of a rather unique organization in Ushahidi, where we decided early on that how we’d run the organization was that we would trust each other and expect that everyone would act like responsible adults. It’s worked brilliantly, even as we’ve grown and spun up new enterprises and organizations such as iHub and BRCK.

Yesterday I read about the Berkshire Hathaway “strategy of trust”:

Mr. Munger, 90, was ruminating on the state of corporate governance, offering a counternarrative to the distrustful culture of most businesses: Instead of filling your ranks with lawyers and compliance people, he argued, hire people that you actually trust and let them do their job.

It’s well worth a read, and I didn’t expect to find parity in leadership philosophy between us and a 300,000-person family of organizations.

How do we do it?

There are probably other organizations like ours, ones who have decided to trust their team and assume that people make good decisions based out of the best intentions of the organization and their colleagues, over themselves. We didn’t set out with a great body of knowledge on how to do this, but instead with some theories that we’ve refined over time. Here are the most important ones:

Find the Right People

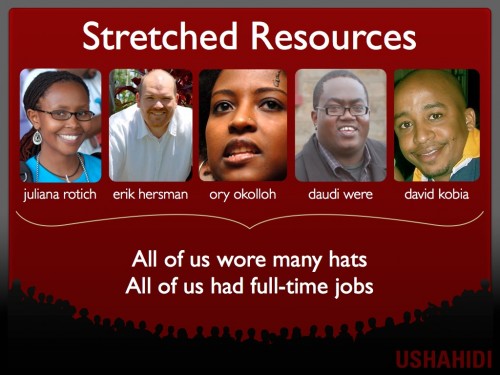

David, Juliana and I particularly don’t like to micromanage. We’ll work with you to define the goal, but if you expect someone to tell you how to get there, you won’t fit. We don’t check up on you all the time, you tell us when there’s a snag. You need to work autonomously. We’ll help, and are always there for a conversation, but your job is to get from point A to point B.

It’s always better to find people who are smart and get things done, who can work autonomously and tend to not put themselves first. Big egos don’t go well with this kind of team, so we look for humility when interviewing.

I remember making a mistake back in 2009, hiring someone off of reputation and resume, without really digging into their portfolio or doing multiple interviews. Ever since then I’ve refused to look at CVs or resumes and each new person goes through about 4-5 other people on the team before we make the final decision. Those other people on the team catch things I wouldn’t, some about skill, but most about ethos and personality.

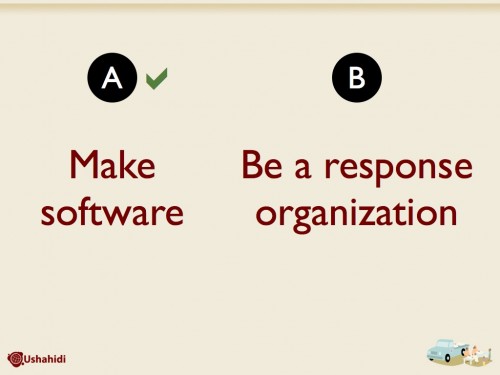

Knowing the Ethos

If an emergency happens where you are, can you make a decision and run with it, without having to ask permission? You should be able to. This is especially important in an organization with a globally distributed team that deals with crisis and disaster. We decided that everyone should be able to make critical decisions about deployments of the software, partnerships and strategic steps on their own. Just fill everyone else in on it as it comes up and if adjustments need to be made, then we do it together.

To make this work, we had to ensure that everyone on the team, from junior engineers to new QA staff actually understood the foundational elements of the organization. Not just what we built, but why we built it, how it all started and where we were going in the future. While there’s no “intro to X” classes, we do throw you in the deep end early on. It started with our first hire, Henry Addo from Ghana, who found himself speaking in the French Senate in Paris in his first month on the job. That made us realize that public speaking forces you to learn a lot more about the organization that you’re in, quickly.

Our goal is that a camera and mic can be put in front of any team member and they can answer any question on the organization. The way they answer it might be different than me due to speaking styles, but because they understand the ethos of the organizations, it is still correct.

Per Diems

We don’t do per diems. You’re traveling for the organization, spend what you need on food, lodging and transport. Be responsible about it, since this is money needed for the organization to grow. If you’re in NYC, we know things are more expensive, if you’re in Omaha we know they’re not. The “Agency Effect” (or Principal Agent Problem) comes into play here as the incentives are wrong between a team member and the organization if they get an allowance for travel.

Final Thoughts

I suppose what I’m saying is that if you truly trust people to act like the adults they are and to do the right thing, they generally do. All the corporate oversight you can apply won’t stop an Enron from happening, so something else has to work. It has to be something that’s real though, people can sniff out very quickly if it’s a manufactured, or fake, trust. This means as much of the onus lies on the leaders to “let go” as it does for the team members to shoulder and own the expectations that come with their role.

My greatest takeaway from the Mr. Munger and Mr. Buffett was found in the last paragraph:

Mr. Munger, in a previous annual meeting, contended that the best way to hold managers accountable is to make them eat their own cooking. Mr. Munger pointed to the late Columbia University philosophy professor, Charles Frankel, who believed “that systems are responsible in proportion to the degree in which the people making the decisions are living with the results of those decisions.” Mr. Munger cited the Romans, “where, if you build a bridge, you stood under the arch when the scaffolding was removed.”

We all need to stand under our own bridges more often, and I’m going to figure out how to make that happen in my organizations.