We tend to think of success in terms of visible growth. That’s not always how it works, it’s not always what you see that matters, and it can be deceiving to think so.

“The widest watering hole isn’t always the longest lasting. The deepest is.”

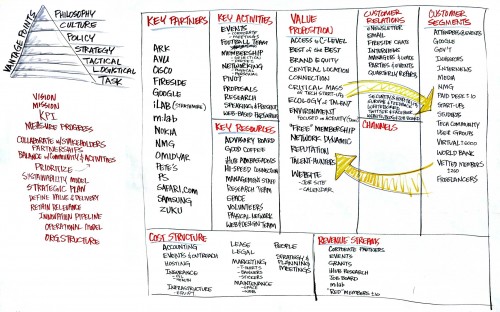

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately as I deal with my own organizations (Ushahidi and the iHub), as well as the startups that I come across. What we use to measure success can actually be a deterrent to real strong growth, growth that isn’t seen immediately, but that creates a much stronger organization and a better future.

An Ushahidi Example

For instance, with Ushahidi we set metrics on “deployments” of the software. Tracking this allows us to say things like, “Ushahidi has 40,000+ deployments in 159 countries around the world”, which is a nice marketing line. At first glance, that seems to be a good number to measure, and it is, but it should only be part of the overall definition of success.

A couple weeks ago we started to revisit our metrics, the numbers we track to see how we’re doing. To understand the real value of Ushahidi’s tools, while new deployments are good to track and are part of the overall picture, we find it’s much more telling how “active” each deployment is. This means how often it’s being used, how many new reports are coming in, how many new versus returning users it has, etc. It’s good for us to know if a deployment was “active” for a short time and then not be used anymore, or if it’s long-term. No judgement is made on that, as we know that sometimes Crowdmaps or Ushahidi are setup for spot needs over a short amount of time, and for long-term needs. Most importantly it helps us understand and differentiate between deployments setup for experimentation, with no use, from those that are useful.

In short, we get a better understanding of the value of our software when we measure “activity” than when we use a broad-brush metric like “total deployments’. We’re now in the middle of adjusting these metrics.

Deeper Waters

The largest organizations aren’t always the most profitable, nor the loudest the most impactful.

FrontlineSMS is a small non-profit tech company that makes software for grassroots NGOs around the world. There are thousands of NGOs, in some of the most challenging places in the world, who are now able to use SMS messaging to better communicate internally and/or externally because they exist. They’re small though, with less than 20 people on their team and they’re not the loudest organization either, yet have had a massive impact on the world.

Lifestraw is an NGO that makes a device to clean water by sucking through a straw. They’ve got big money, loud voices and have a solution that seems ingenious and sexy at the same time. They’ve made a lot of noise, and maybe even have figured out a way to make money using carbon offsets (which I think is brilliant), but are fairly useless and don’t have much impact at all.

There are other examples, such as the size of the Wikipedia’s team and budget, and how they’re one of the most influential websites in the world. Or we could talk about how the startup Color raised a whopping $41m and fizzled.

In Kenya’s startup scene I think about how we get caught up in how much money a company has raised, but don’t discuss how much revenue they’ve brought in. We also tend to get sidetracked into thinking about how much something is written about in the papers and not looking at their user numbers or whether or not anyone outside of the Twitterati are using it. There will be discussions on how, “someone got funding, but there’s nothing to show for it”, meanwhile they’ve been building away on a backend for clients that the public doesn’t get to see.

We need to get into more discussions that are nuanced, ones that are beyond one-size-fits-call metrics and more on how we define growth and success.

That’s the wrong model for us. Instead, we should look closer at the

That’s the wrong model for us. Instead, we should look closer at the