If you provide services to poor people, should you make a profit?

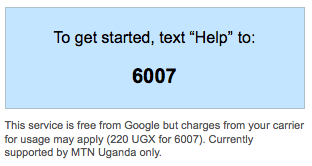

That’s essentially the question raised by Katrin Verclas on MobileActive, and it’s an excellent one. Specifically, Katrin calls out the new Google Trader service offered by Google in Uganda, in conjunction with the release yesterday of their SMS products with Grameen and MTN Uganda, one of the local mobile phone operators. Basically, they charge 220 Ugandan Shillings per use, instead of the median 110 UGS charge across most networks. This is called a premium SMS rate.

Premium SMS rates are charged so that third-party service providers can make money off of services that they provide over the mobile phone network. The operator makes their (ridiculously high) profit as normal, and the overage is for the third-party. You’ll find a lot of dating, event and sports services offered in this way all over the world, not least across Africa.

Back to the question

The question posed is if people who are claiming to help the poor should charge, and if so, should they make a profit?

I think we’ve seen from the Grameen model in Bangladesh (ex: Grameen Bank and Grameen Phone’s Village Phone program) that you can (and possibly should). By doing so you help both parties; first, by providing a service that consumers value and are willing to pay for, and second by making the business of running an operation self-sustaining. Many good business, or project, ideas die due to lack of sustainable cash flow.

For instance, if a 220 shilling SMS can save you the 1500 shilling visit to the doctor or veterinarian, or give you a 10% higher return for your crops, is it worth it?

Is there a problem in the question?

There ends up being a paternalist nuance to that original question. After all, is it up to us to decide what services to offer the poor and at what price? Aren’t poor people able to make the value-based decision on whether a trip to the doctor is more useful to them than a call or an SMS to one? If services are being offered, the person making the decision to call, SMS or go physically to solve their problem, or not, is ultimately the arbiter of whether or not a service has merit and should be offered. It’s a classic market-led approach – if the price is too high for the service, equilibrium will not be reached and one will give, usually price.

This is particularly true when talking about for-profit companies offering services – like Google is with Google Trader. They don’t operate under the same development/grant funded subsidization that a lot of others do in Africa. Even if their goal was not to make a profit on this service, they still need to cover internal costs, as does every organization that isn’t provided with free money.

Final thoughts

This space in Africa, of offering services to the poor (in lieu of the governments actually doing their jobs), has been primarily “owned” by large development and aid organizations. This has created a false floor for the economy, as projects and initiatives are propped up by outside money and services rarely have to survive on their own. This is changing, as low cost and high value options come into the market, be they mobile phone operators providing new communication opportunities, or cheap chinese batteries and LED lights for local energy/lighting needs.

I’m sensing a flux in the space, like two bull buffaloes before they fight, the heavyweights in the aid industry and in business are circling each other before they knock heads. The marketing is over who is helping the poor and marginalized in Africa best. In the end the market will decide, and regardless of the messages spouted by both sides, the “poor African” will choose the winner.

If there’s a problem with collusion and price fixing in an industry (like there sometimes seems to be with SMS services in a country), that’s something beyond the scope of individuals and needs to be tackled separately by regulation. However, that’s not the case here, we have expensive SMS services in East Africa, but the new entrants into the space always offer low rates, and the costs of switching providers is relatively low.

No, this is market-based competitive services and both non-profits and for-profits have the right to offer them at whatever price they like. Equally, individuals have the right to use it or not, be they premium SMS rates or not.

I’d like to hear some other African’s thoughts on this.

Do you want big multinationals like Google and MTN coming in and providing their services to you? Should we be asking questions for the poor, or is that condescending in itself? What is the sticking point here, and is there a side that I’m missing?

**UPDATE**

Thanks to Katrin’s email to Rachel Payne, Google’s lead in Uganda, we have the following response from her on this topic, and it does clarify quite a few unknowns:

Hi Katrin.

Yes, I saw your blog post where you speak in detail about the pricing. However, what is written is not quite accurate. You see, Google, Grameen and MTN launched three types of mobile services yesterday: Google SMS Tips (targeting low-income, rural users primarily), Google SMS Search (urban, mainstream) and Google Trader (all users).

The second service is somewhat similar to other “premium SMS” content services currently available (except that it is built on Google search technology) and therefore, is the same price as other content services. To accommodate the first group, we have priced Google SMS Tips at half the price of a content service; this is available for the cost of a person-to-person SMS, which many rural individuals are willing and able to afford currently.

The third service drives income and livelihood benefits, so we decided to begin charging at the normal content service rate and monitor whether this excludes rural communities or not (we did extensive testing during the pilot, which included pricing discussions and most of the users found that Google Trader provided far greater, direct value than the 110 shilling price difference). For all services, we are offering them for free for the first few months, just to ensure that all users have an equal opportunity to try them out, risk-free and allow them to access critical content during this period so that they can assess whether or not they would like to continue to use the service.

I hope this helps provide a bit more information that clarifies the questions raised.