Maker Faire Africa 2012 in Pictures from WhiteAfrican on Vimeo.

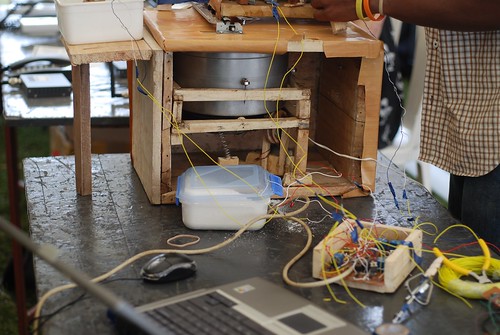

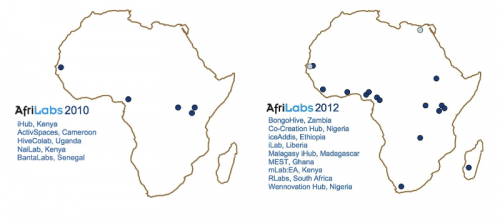

I’ve long been a proponent of getting more spaces set up for hardware prototyping and making of things in Africa. I wrote about it first in 2010 (Hardware hacking garages), then again in 2012 (Fab Factories: Hardware Manufacturing in Africa). I’m one of the founding organizers for Maker Faire Africa and the founder of AfriGadget. I’m not just writing about it either, as we have plans to open up a makerspace in Nairobi this year, which will compliment the FabLab that we already have at the University of Nairobi.

Well managed makerspaces are a missing component in the African technology ecosystem and we need more of them.

There’s a couple reason’s that we need more of them.

First is for youth and learning, like the urine powered generator story from the teenage girls in Lagos, that took the world’s bloggers by storm, is an example of this. Another is the young Kenyan who used a simple lighting mechanism to scare away lions. We need places where young people can get their hands into hardware earlier, not all schools are setup for this, and having places with good mentors and tools that they couldn’t buy on their own is important.

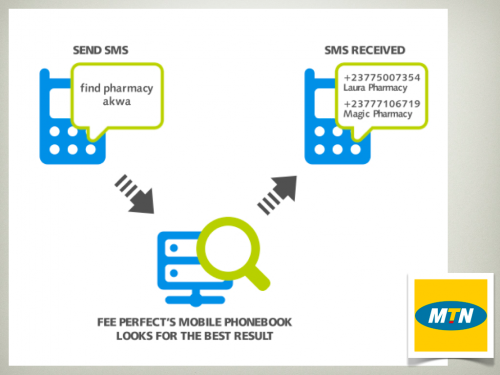

Second is about a culture we already have of making things in Africa, specifically that we need to acknowledge our already present maker culture and then try to move it in the direction where it melds some of the more recent high-tech advances with the already low-tech inventiveness found locally. Examples abound, take the bladeless wind turbine out of Tunisia, or the mobile phone security system for your car in Kenya. Simply put, the more we get merge the hardware and software, the more interesting our products will be and they’ll have more global relevance at the same time.

A False Dichotomy

I just read an article titled “Close the Incubators and Accelerators, Open FabLabs and MakerSpaces instead” by Mawuna Remarque Koutonin. While overall it’s a good piece, the title does it a disservice by assuming a false dichotomy – that one is better than the other. It’s not an either/or, it’s an “and”. We don’t need to get rid of accelerators and incubators for software development, we need to add more makerspaces for hardware development and experimentation on top of what we already have.

First a quick list of assumptions that aren’t properly addressed in the piece, so are confusing:

- There is a conflation of the terms “incubators” and seed-funding “accelerators” they are two different spaces and ways of growing businesses.

- Makerspaces are collaborative incubation and experimentation spaces with a hardware prototyping focus.

- Startups can be software or hardware based (or both).

- Incubation and acceleration is not tied to just only one type (software or hardware) of startup.

- Not all companies or individuals benefit equally from incubation, some not at all.

- It can be argued that hardware startups benefit more from incubation facilities due to the heavy cost of getting started.

Other things to consider regarding software, hardware and ultimately the entrepreneurs and companies that come from them:

They’re different. Software startups are different than hardware startups, very different. I know this due to being involved with a hardware product internally at Ushahidi, it’s not the same at all and the needs for the two are completely different.

Having a space doesn’t take the place of personal drive and ambition. Incubators are no substitute for hungry entrepreneurs getting their startup going. Hackerspaces are no substitute for inquisitive hardware minds to experiment. Both require people driven towards a goal already, the space doesn’t matter if the person isn’t ready.

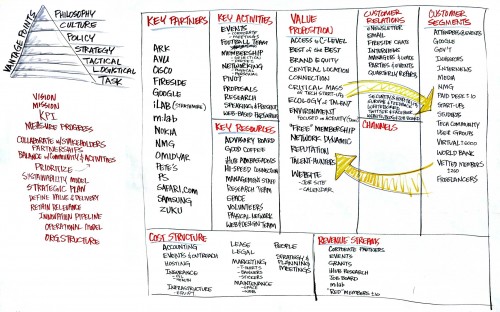

Both can help accelerate entrepreneurs. Both incubators and makerspaces give driven people a chance to move further, faster. The basics of fast internet, space to work with like-minded people, access to tools, inroads to mentors and/or business contacts, and government or university connections are all things that both can (should?) provide.

The conflation of what these spaces are is understandable, as they seem to be morphing all the time. Two good pieces to consider:

“Hackerspaces as Accelerators”

“It makes good theoretical sense to use a hackerspace as part of an accelerator. Incubators and accelerators are constantly evolving from models that provide premises, training and funding, that may or may not be part of a larger organization, to models that provide nothing but a cooperative community sharing resources. Some take equity, some ask for rent. Some take cuts at both ends. Some have sliding payment scales and operate in tranches, others have fixed programs. There are a lot of variations and not all accelerators/incubators deliver value.”

“Evaluating the Effects of Accelerators? Not So Fast”

“A business incubator in the purest sense refers to an office park or building complex that charges businesses, typically new businesses that cannot afford their own offices, some rent in exchange for space within the incubator and some administrative services and infrastructural support.”

“Accelerators are organizations that provide cohorts of selected nascent ventures seed-investment, usually in exchange for equity, and limited-duration educational programming, including extensive mentorship and structured educational components. These programs typically culminate in “demo days†where the ventures make pitches to an audience of qualified investors.”

Where should they be?

In short, not the universities in Africa. They’re mired in the 1970’s and have levels of bureaucracy that make it difficult for innovative products or companies to grow out of them. I’d like this to be different than it is too. When I look at what we’ve built at the iHub over the past couple years (the UX Lab, Research arm, supercomputer cluster), I can’t help but think that if Kenyan universities were doing their jobs, then we wouldn’t have to do a lot of these things.

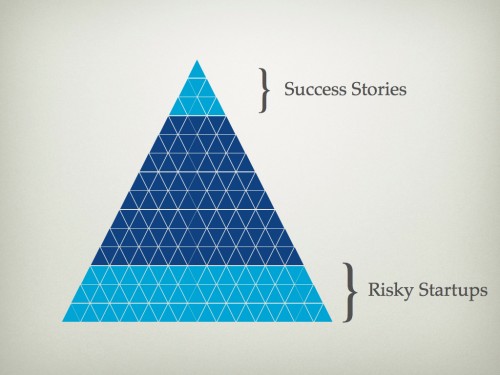

The truth is, globally there are few universities that do a good job of incubation. There are few labs that do a good job of prototyping and taking products to market. There are few accelerators that do a good job of accelerating startups. It doesn’t mean you throw all intent of doing these activities away due to 90% being bad at what they do. That doesn’t mean all are bad. It just means we need to emulate the good ones better.

The best incubators and makerspaces I’ve seen, or have been a part of, are collaborative community environments. Caterina Mota provides an excellent talk describing why they work, and uses the stories of Safecast and Makerbot to underline her statement:

“Secrecy and exclusivity are not essential to commerce.” Catarina Mota

It’s important for us to have spaces that the community has built and runs, where the university, corporates and government can plug into, but not be in charge of.

Jonathan Kalan said it best in his recent article researching the tech hub boom across Africa:

“In a region with a near-total absence of true “3rd spacesâ€- physical spaces like coffee shops, libraries, and internet cafes, Africa’s “hub boom†has emerged to fill the gap, fostering openness, access, collaboration, education and sharing in Kenya’s tech community, while offering nodes for international exchange, where people like Eric Schmidt can drop in to get a sense of what’s going on.

Crucially, they address the ecosystem’s essential need to grow startups beyond ideas. There is no shortage of entrepreneurs with great ideas on the continent, yet many lack the knowledge and skills to build and scale companies. Through workshops, accelerator programs, incubators and mentorship, these hubs are helping to building local capacity.”

In the end, that’s what we’re all driving for. We’re looking to build and grow the spaces and investment vehicles that allow Africa’s tech community to expand and grow, whether it looks like a makerspace, an incubator or a seed-funding accelerator. We don’t need less of anything, we need more and we need diversification in the types of spaces as they help grow companies in different fields.