TL;DR – Kenya’s IEBC tech system failed. I started a site to collect notes and facts, read it and you’ll be up to date on what’s currently known.

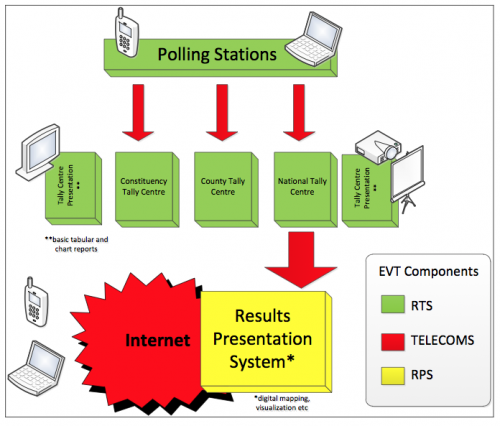

Kenya’s IEBC (Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission) had an ambitious technology plan, part based on the RTS (Results Transmission System), part based on the BVR (Biometric Voter Registration) kits – the latter of which I am not interested in, nor writing about. It was based on a simple idea that the 33,000 polling stations would have phones with an app on them that would allow the provisional results to be sent into the centralized servers, display locally, and be made available via an API. It should be noted that the IEBC’s RTS system was a slick idea and if it had worked we’d all be having a much more open and interesting discussion. The RTS system was an add-on for additional transparency and credibility, and that the manual tally was always going to happen and was the official channel for the results.

On Tuesday, March 5th, the day after the elections, the IEBC said they had technical problems and were working on it. By 10pm that night the API was shut off. This is when my curiosity set in – I didn’t actually know how the system worked. So, I set out to answer three things:

- How the system was supposed to work (Answer here)

- Who was involved and what they were responsible for (Answer here)

- What actually failed, what broke (Answer here)

Turns out, it wasn’t easy to find any answers. Very little was available online, which seemed strange for something that should be openly communicated, but wasn’t. We all benefit from a transparent electoral process, and most especially for transparency in the system supposed to provide just that.

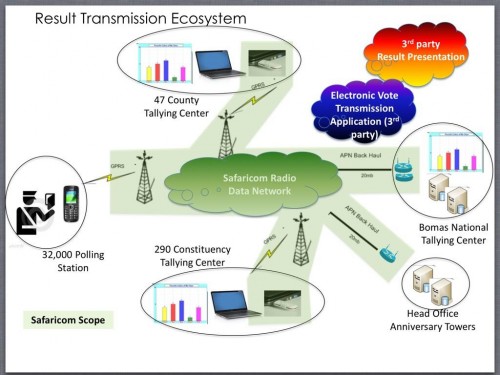

So, I set up a site to ask some questions, add my notes, aggregate links and sources, and post the answers to the things I found on the RTS system. I did it openly and online so that more people could find it and help answer some of the questions, and so that there would be a centralized place to find the some facts about the system. By March 6th, I had a better understanding of the flow of data from the polling stations to the server and the API, and an idea of which organizations were involved:

- Polling station uses Safaricom SIM cards

- App installed in phone, proprietary software from IFES

- Transmitted via Safaricom™s VPN

- Servers hosted/managed by IEBC

- JapakGIS runs the web layer, pulling from IEBC servers

- Data file from IEBC servers sent to Google servers

- Google hosted website at http://vote.iebc.or.ke

- Google hosted API at http://api.iebc.or.ke

- Next Technologies is doing Q&A for the full system

Why now? Why not wait a week until the process is over?

It’s been very troubling for me to see people speculating on social media about the IEBC tech system, claiming there have been hackers and all types of other sorts of seeming misinformation. Those of us in the technology space were looking to the IEBC and its partners for the correct information so that these speculative statements could be laid to rest. I deeply want the legitimacy of this election to be beyond doubt. The credibility of the electoral system was being called into question, and clear, detailed and transparent communications were needed in a timely manner. These took a long time to come, thus my approach.

Interestingly, Safaricom came out with a very clear statement on what they were responsible for and what they did. Google was good enough to make a simple statement of what their responsibilities were on Tuesday. both of these companies helped answer a number of questions, and I hoped that the other companies would do the same. Even better would have been a clear and detailed statement from the head of IEBC’s ICT department to the public. Fortunately they did provide some general tech statements, claimed responsibility, refuted the hack rumor, and made the decision to go fully manual.

My assumption was that since this was a public service for the national elections, that the companies involved would be publicly known about as well. This wasn’t true, it took a while asking around to get an idea of who did what.On top of that, In a country that has been expounding on open data and open information, I was surprised to find that most of the companies didn’t want to be known, and that a number of people thought it was a bad idea to go looking for who they were and what they did. I wasn’t aware that this information was supposed to be secret, in fact I assumed the opposite, that it would be freely announced and acknowledged which companies were doing what, and how the overall system was supposed to work.

I’ve spoken directly to a number of people who are very happy that I’m asking questions and putting the facts I find in an open forum, and some that are equally upset about it. Much debate has been had openly on Skunkworks and Kictanet on it this, and when we debate ideas openly we fulfill the deepest promise of democracy. My position remains that this information should be publicly available, and the faster that it’s made available, the more credible the IEBC and it’s partners are.

By Friday, March 8th, I had the final response on what went wrong. My job was done. Now it’s up to the rest of the tech community, the IEBC and the lawyers to do a post-mortem, audit the system, etc. I look forward to those findings as well.

Finally, I’ll speculate.

My sense of the IEBC tech shortcomings is that it had very little to do with the technology, or the companies creating the solution for them. It was a fairly simple technology solution, that had a decent amount of scale, plus many organizations that needed to integrate their portion of the solution. Instead, I think this is a great example of process management failure. The tendering process, project management and realistic timelines don’t seem to have been well managed. The fact that the RFP due date for the RTS system was Jan 4, 2013 (2 months exactly before the elections) is a great example of this.

Some are saying that the Kenyan tech community failed. I disagree. The failure of the IEBC technology system does not condemn, nor qualify, Kenya’s ICT sector. Though this does give us an opportunity to discuss the gaps we have in the local market, specifically the way that public IT projects are managed and the need for proper testing.

It should be said that all I know is on the IEBC Tech Kenya site, said another way, read it and you know as much as me. There is likely much more nuance and many details missing, but which can only be provided by an audit or the parties involved stepping forward and saying what happened.