We’re about to ship our first orders of BRCKs next week, on July 17th.

Tomorrow (Wed, July 9th) we have a launch event happening at Sarit Centre for our Nairobi friends and media, starting at 9am, where we take over our partner Sandstorm‘s store for the day. We’ll be there all day, so come on buy if you can make it. You’ll be able to use the devices and ask questions from anyone on the BRCK team.

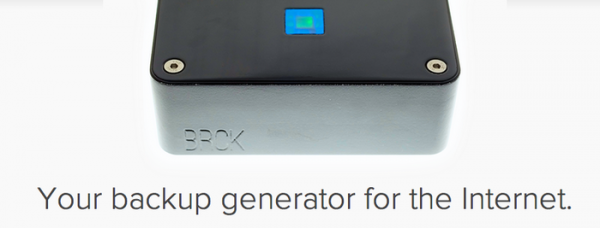

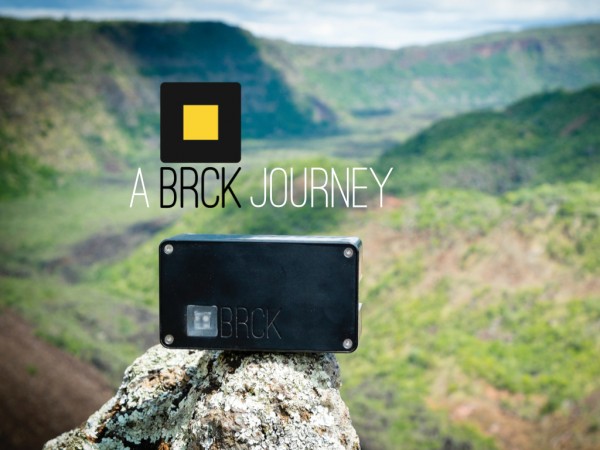

The BRCK is a rugged, self-powered, mobile WiFi device which connects people and things to the internet in areas of the world with poor infrastructure, all managed via a cloud-based interface.

It is designed and engineered right here in Nairobi, with components from Asia, and final assembly done in the USA. Specs here.

the Journey

Most people heard about the BRCK a year ago when we ran our Kickstarter campaign that raised $172k. What a lot of people don’t know is that the journey started long before that, 1.5 years earlier in fact.

Back in November of 2011 I was in South Africa for AfricaCom, and it was in a discussion with my good friend Henk Kleynhans (the founder and then-CEO of SkyRove) that we started talking about routers. Knowing nothing about routers, I asked him why he didn’t build his own, to which I think the answer was something like, “that’s hard” and it wasn’t their core business anyway.

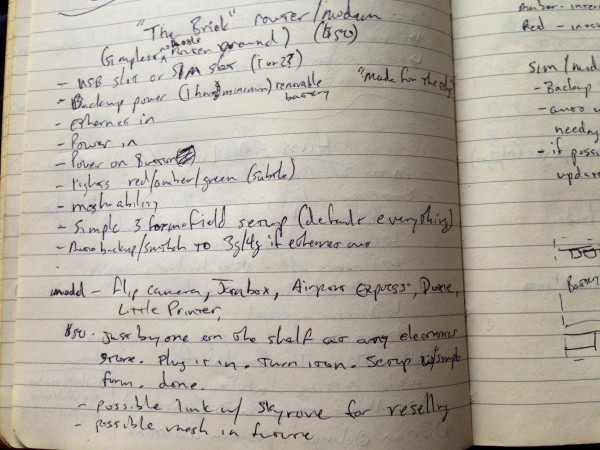

Later on that evening I was flying back to Kenya and I started pondering what it would be like if we built a router made for our own environment – something that would give us good solid connectivity in Africa. I started sketching out the first ideas around what would be in the BRCK, what it would need, etc. When I landed in Nairobi, I started talking to the Ushahidi team about this, and whether anyone wanted to try prototyping this with me in their free time.

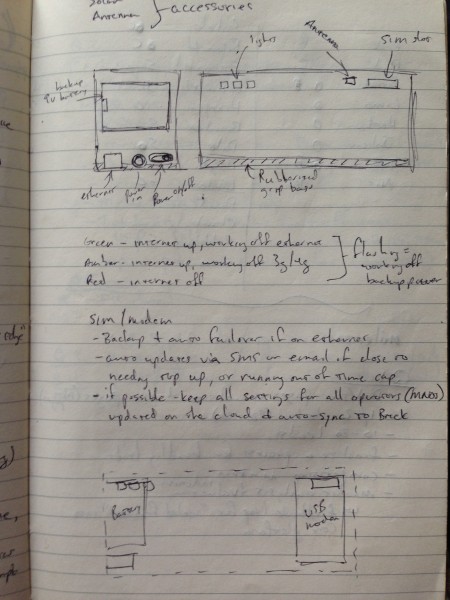

My initial notes on the BRCK in the airplane, thinking through what it should be, basic features, and products I liked.

Initial BRCK sketch, drawn in my notebook in November 2011. You can tell I hadn’t a clue as to where things should go yet, it was just barebones features and simplicity was key.

With the problems we have around power and reliable internet connectivity in Nairobi, we all had an itch to do something, and so we did.

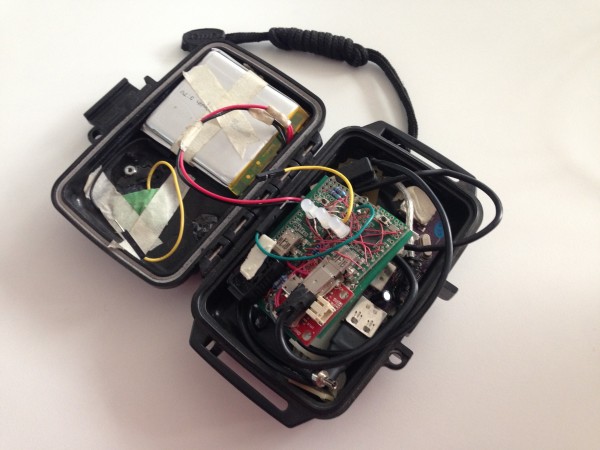

The 1.5 years between that point and the Kickstarter was filled with Jonathan Shuler doing a number of early prototypes, Brandon Rosage hammering out an early brand and design, and Brian Muita getting into the guts of the software. Sometime in there was a walk with Ken Banks in a field in Cambridgeshire, discussing what this future product could be as a company. Then there was the entry of Philip Walton, volunteering his time to do the first truly functional designs that married the components and some customized firmware, throwing it all into an Otterbox case, held together by Sugru and tape, to make sure it worked (seem image below). Then Reg Orton came along in late 2012 and started volunteering his time and knowledge around case and PCB design, and started to professionalize our hardware production. All of this culminated in a working prototype.

An Early BRCK Prototype from mid- 2012

We ran the Kickstarter in June last year to test the market, to see if there were others who thought this BRCK device was cool, useful and something that they would purchase. It worked out well, and we found out that there were a number of business types who wanted something just like this.

Then the real work began.

From Prototype to Production

It’s fairly easy today to prototype a cool new device, we did that for 1.5 years with many iterations even before we did our Kickstarter in June last year. When you go to production though, that’s a whole different beast, and we ended up spending a year from our Kickstarter until today going through more levels of prototypes before we finalized on our production-level hardware back in February. Keep in mind, that’s with people on the team, like our CTO Reg Orton, who have been in this hardware space for 12+ years.

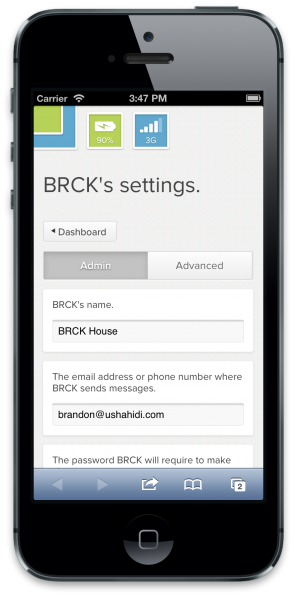

There’s also the software integration issue that had a lot of unknowns which we couldn’t tell in advance. It’s not just hardware we’re building but an integrated software and hardware package that consists of hardware + firmware + cloud. Fortunately we’ve got some pretty amazing problem solvers who don’t seem to sleep on our team, between the heroics of our COO Philip Walton and cloud lead Emmanuel Kala, we were able to find workarounds and put together a robust BRCK management package.

What I’m getting at is this – software is hard to get done well. Hardware is harder. Software plus hardware is amazingly complex, and it’s easy to underestimate the level of difficulty in what seems like a simple device.

It’s been a battle, one with multiple fronts and many setbacks along the way. We’ve had our modem supplier go end-of-life on one of our core components, and subsequently had to find a new supplier and redesign our board and case. We’ve found crazy bugs in OpenWRT that took us weeks to figure out a way to work around. We’ve mixed in some fairly harsh testing of the BRCK in some of Kenya’s hardest environments, and we’ve seen it perform and change the way a business can do their work. We’ve also seen our earliest users loading up education materials on it for schools that aren’t fully on the grid.

Rachel running on a BRCK in Uganda, by Johnny Long (more on their Education page).

We’re finally there, after many, many months.

Some Thanks

It’s with great gratitude to my BRCK partners and team that I say thanks for pushing through. I’m also extremely grateful to Ushahidi, especially David and Juliana, and the Board, for helping push the BRCK through, even in those early days of 2012 when it seemed so crazy. None of this could have been done without a few brave souls willing to risk some money on us, to our seed round of investors who came together and put in $1.2m, which meant we could hire more people and build an amazing team.

Finally, our biggest debt of gratitude goes to our early backers, those of you who over a year ago put some money into this little black box. You will have your BRCKs soon, and we hope that they live up to your expectations. After all this time, I can say I’m probably more excited about getting them into your hands than you are in getting them! 🙂